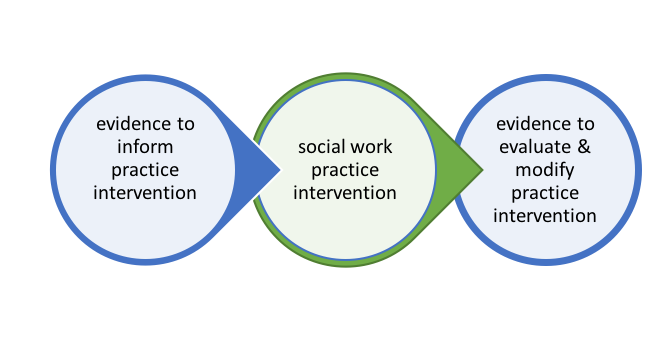

The right-hand side of the evidence-intervention-evidence figure from Chapter 1 (Figure 1-1) is the focus of this chapter.

In Chapter 2 we looked at evidence-informed practice decisions. In this chapter, we introduce information about evaluating practice, what other disciplines call data-based or data-driven decision making: using data and evaluation research methods to make social work practice accountable and to inform practice improvement efforts.

In this chapter you will learn:

In short, social work professionals engage in evaluation of practice as an accountability issue. We are accountable to clients, programs, funders, policy decision-makers, and the profession to ensure that we are delivering the best possible services, that the services we deliver achieve the promised benefits, and that the resources dedicated to our services are well-spent. This has previously been covered in our discussions regarding standards presented in the Social Work Code of Ethics. Of particular relevance to this discussion is the Standard 5.02 concerning evaluation and research (p. 27). Social workers are expected to evaluate policies, programs, and practice interventions, as well as facilitate research that contributes to the development of knowledge.

Throughout the remainder of our course Research and Statistics for Understanding Social Work Interventionwe examine methods for evaluating intervention efforts. A framework for understanding different approaches to evaluation is helpful, beginning with the nature of the evaluation research questions and exploring how these relate to different forms or approaches to evaluation.

Evaluation Questions. By now you recognize that research designs and methodologies are driven by the nature of the research questions being asked. This is equally true in the evaluation research arena. Here is a sample of the kinds of questions asked in evaluating social work practice at different levels:

Evaluation Formats. Because evaluation questions differ, social workers employ varied formats for engaging in evaluation. Here is a description of four major forms of evaluation research: needs assessment, outcome evaluation, process evaluation, and cost-effectiveness evaluation.

Needs assessment. The aim of needs assessment is to answer questions related to the scope of a problem or need and where gaps exist in efforts to address the problem or need. For example, school social workers may want to know about the problem of bullying that occurs in a school district. They might engage in a needs assessment to determine the nature and extent of the problem, what is needed to eradicate the problem, and how the problem is being addressed across the district. Where they detect sizeable gaps between need and services provided, social workers can develop targeted responses. The needs assessment might also indicate that different responses need to be launched in different circumstances, such as: elementary, middle, and high school levels; or, parents, teachers, administrators, peers, and mental health professionals in the district; or, different neighborhood schools across the district. Needs assessment is often concerned with the discrepancy between what is needed and what is accessed in services, not only what is offered. As proponent of social justice, social workers are also concerned with identifying and addressing disparities (differential gaps) based on income, race/ethnicity, gender/gender identity, sexual orientation, age, national origin, symptom severity, geographical location (e.g., urban, suburban, rural disparities), and other aspects of human diversity. This represents an important extension of what you learned in our earlier course, Research and Statistics for Understanding Social Work Problems and Diverse Populations. The gap between two sides or groups is sometimes monumental.

Outcome evaluation.Evaluating practice outcomes happens at multiple levels: individual cases, programs, and policy. Social work professionals work with clients or client systems to achieve specific change goals and objectives. For example, this might be reducing a person’s alcohol consumption or tobacco use, a couple having fewer arguments, improving student attendance throughout a school, reducing violence in a community, or breaking a gender or race based “glass ceiling” in an institution. Regardless of the level of intervention, social work professionals evaluate the impact of their practices and intervention efforts. This type of research activity is called outcome evaluation. When outcome evaluation is directed to understanding the impact of practices on specific clients or client systems, it is called practice evaluation.

Evaluating the outcomes of interventions also happens at the aggregate level of programs. Social workers engaged in program evaluation look at the impact of an intervention program on the group of clients or client systems it serves. Rather than providing feedback about an individual client or client system, the feedback concerns multiple clients engaged in the intervention program. For example, social workers might wish to evaluate the extent to which child health goals (outcomes) were achieved with an intervention program for empowering parents to eliminate their young children’s exposure to third-hand smoke. The background for this work is described in an article explaining that third hand smoke is the residue remaining on skin, clothing, hair, upholstery, carpeting, and other surfaces; it differs from first- or second-hand smoke exposure because the individuals are not exposed by smoking themselves or breathing the smoke someone else produces. Young children come into close contact with contaminated surfaces when being held by caregivers, riding in vehicles, or crawling and toddling around the home where smoking has occurred, leaving residue behind (Begun, Barnhart, Gregoire, & Shepperd, 2014). Outcome oriented program evaluation would be directed toward assessing the impact of an intervention delivered to a group of parents with young children at risk of exposure to third-hand smoke at home, in transportation, from relatives, or in child care settings.

Policy evaluation has a lot in common with program evaluation, because policy is a form of intervention. Policy evaluation data are based on intervention effects experienced by many individuals, neighborhoods, communities, or programs/institutions taken together, not tracking what happens with one client system or a single program at a time. For example, communities may gather a great deal of evaluation data about the impact on drug overdose deaths related to policies supporting first-responders, family members, friends, and bystanders being able to deliver opioid overdose reversal medications (naloxone) when first encountering someone suspected of experiencing opioid overdose. “As an antidote to opioid overdoses, naloxone has proven to be a valuable tool in combating overdose deaths and associated morbidity” (Kerensky & Walley, 2017, p. 6). Policy evaluation can answer the question of how much impact such a policy change can make. Policy evaluation also answers questions such as: who should be provided with naloxone rescue kits; how naloxone rescue kit prescribing education might alter opioid prescribing behavior; whether different naloxone formulations, doses, and delivery methods provide similar results and how do their costs compare; how what happens after overdose rescue might keep people safe and link them to services to prevent future overdose events; and, how local, state, and federal laws affect this policy’s implementation (see Kerensky & Walley, 2017). These factors help determine if the impact of a policy is simply a drop in the bucket or a flood of change.

Process evaluation. Process evaluation is less concerned with questions about outcomes than with questions about how an intervention or program is implemented. Why evaluating process matters is clear if you think about fidelity examples previously discussed (e.g., the Duluth model for community response to domestic violence). Process evaluation matters in determining what practitioners really do when intervening and what clients or client systems experience during an intervention. It also matters in terms of understanding the “means to the end,” beyond simply observing the end results. Process evaluation also examines the way an intervention or program is supported by agency administrators, agency activities, and distribution of resources—the context of the intervention—and possible efficiencies or inefficiencies in how an intervention is delivered.

“Process evaluations involve monitoring and measuring variables such as communication flow, decision-making protocols, staff workload, client record keeping, program supports, staff training, and worker-client activities. Indeed, the entire sequence of activities that a program undertakes to achieve benefits for program clients or consumers is open to the scrutiny of process evaluations” (Grinell & Unrau, 2014, p. 662).

For example, despite child welfare caseworkers’ recognition of the critically important role in child development for early identification of young children’s mental health problems and needs, they also encounter difficulties that present significant barriers to effectively doing so (Hoffman et al., 2016). Through process evaluation, the investigators identified barriers that included differences in how workers and parents perceived the children’s behavioral problems, a lack of age-appropriate mental health services being available, inconsistencies with their caseworker roles and training/preparation to assess and address these problems, and a lack of standardized tools and procedures.

Cost-effectiveness evaluation. Cost-related evaluations address the relationship between resources applied through intervention and the benefits derived from that intervention. You make these kinds of decisions on a regular basis: is the pleasure derived from a certain food or beverage “worth” the cost in dollars or calories, or maybe the degree of effort involved? While costs are often related to dollars spent, relevant costs might also include a host of other resources—staff time and effort, space, training and credential requirements, other activities being curtailed, and so forth. Benefits might be measured in terms of dollars saved, but are also measured in terms of achieving goals and objectives of the intervention. In a cost-effectiveness evaluation study of Mental Health Courts conducted in Pennsylvania, diversion of individuals with serious mental illness and non-violent offenses into community-based treatment posed no increased risk to the public and reduced jail time (two significant outcomes). Overall, the “decrease in jail expenditures mostly offset the cost of the treatment services” (Psychiatric Times, 2007, p. 1)—another significant outcome. The intervention’s cost-effectiveness was greatest when offenses were at the level of a felony and for individuals with severe psychiatric disorders. While cost savings were realized by taxpayers, complicating the picture was the fact that the budget where gains were situated (criminal justice) is separate from the budget where the costs were incurred (mental health system).

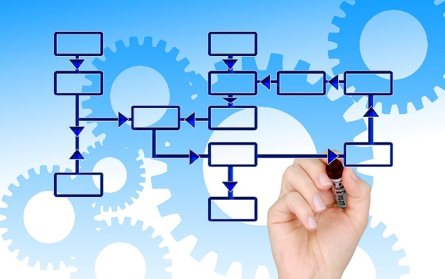

The goals, objectives, and methods of evaluation research and intervention research often appear to be very similar. In both cases, systematic research procedures are applied to answer questions about an intervention. However, there exist important differences between evaluation and research to consider, important because they have implications for how investigators and evaluators approach the pursuit of evidence.

Differences begin with the nature of the research questions being asked. Evaluation researchers pursue specific knowledge, intervention researchers pursue generalizable knowledge. In evaluation, the goal is to inform leader or administrator decisions about a program, or to inform an individual practitioner’s intervention decisions about work with specific clients. The aim of practice or program evaluation is to determine the worth of an intervention to their agency, their clients, and their stakeholders. Intervention researchers, on the other hand, have as their goal the production of knowledge or the advancing of theory for programs and practitioners more generally—not a specific program or practitioner. This difference translates into differences in how the research process is approached in evaluation compared to intervention science. Figure 3-1 depicts the differences in approach, methodology, analysis, and reporting between evaluation and intervention research (LaVelle, 2010).

Figure 3-1. Differences between intervention and evaluation research.

Take a moment to complete the following activity.

In this chapter, you were introduced to why evaluation is important in social work, extending what you learned in the prior course about the relationship of empirical evidence to social work practice. You also learned about the nature of evaluation questions and how these relate to evaluation research—an extension of what you learned in the prior course concerning the relationship between research questions and research approaches. In this chapter you were introduced to four different formats for evaluation (needs assessment, outcome evaluation, process evaluation, and cost-effectiveness evaluation), and you learned to distinguish between evaluation and intervention research.